By Alan Richard, SEF Director of Communications

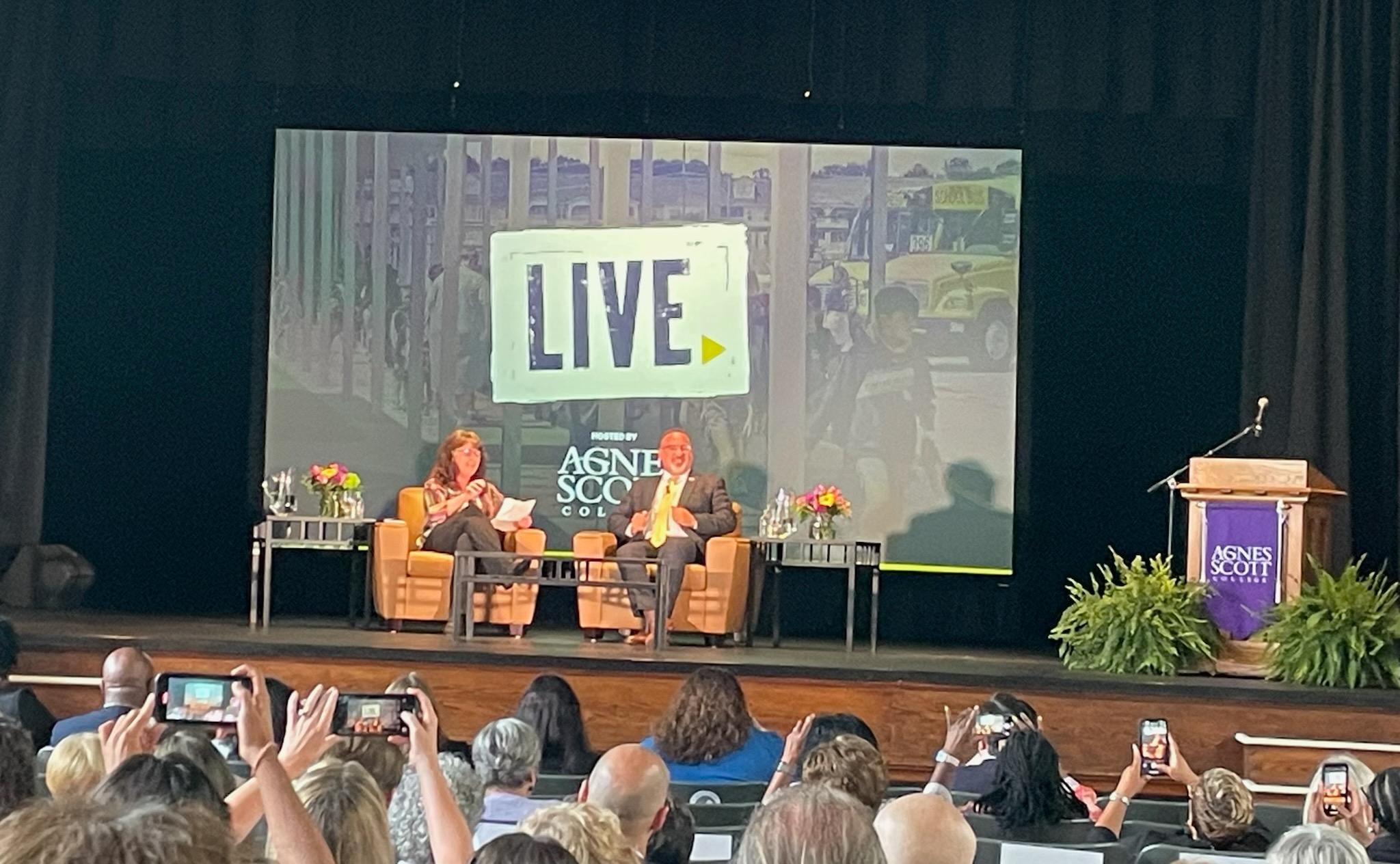

DECATUR, Georgia — Issues of race are still integral to education in this country despite new court rulings and state laws that suggest otherwise, U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona and other leaders said during an Atlanta Journal-Constitution event on July 17 at Agnes Scott College outside Atlanta.

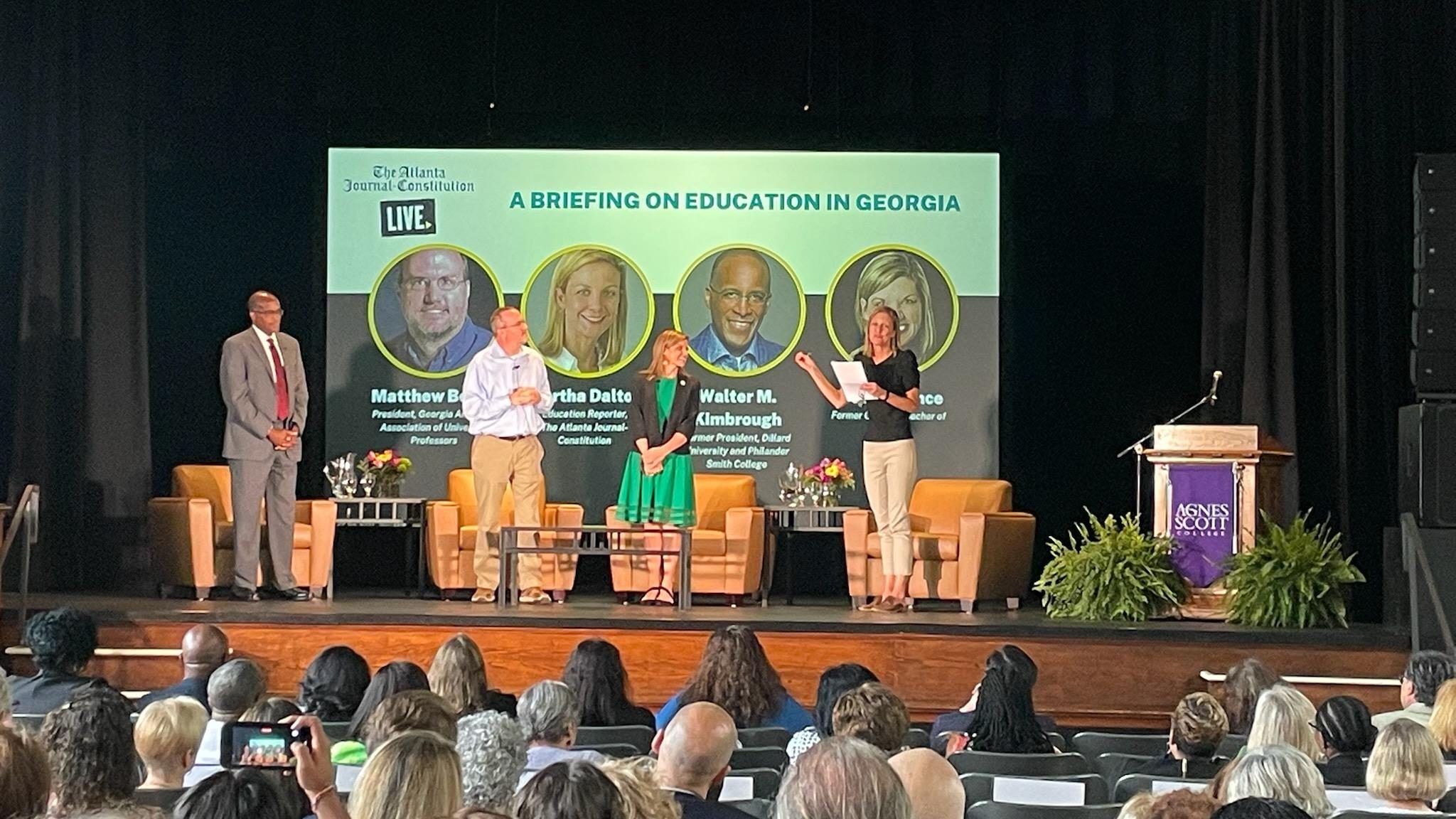

The program began with a question on the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent decision on race-conscious college admissions policies, posed by Martha Dalton, a veteran education reporter now with the Atlanta newspaper.

Walter Kimbrough, a former president of multiple HBCUs and currently the interim director of the Morehouse College Black Men’s Research Institute in Atlanta, asked why the recent high court ruling on race in admissions limited a few historically underserved students — rather than the much higher number of “legacy” students admitted because their families attended the same college or have become major donors.

It’s somehow OK to have special admissions for athletes of color who earn revenue for the university, but not young scholars, he said. “My father couldn’t go to the University of Georgia. I could,” Kimbrough said.

With these trends working against longstanding, basic steps toward diversity, he added, “We’re pulling people apart.”

Rising costs of degrees

University of North Georgia English professor Matthew Boedy, president of the Georgia Conference of the American Association of University Professors, worried that the recent court ruling will lead to more subjective admissions decisions, forcing “drastic changes” in the student demographics in many colleges and universities.

He pointed out that state funding in Georgia and most other states has dropped substantially, drastically increasing tuition and other costs for students over the years.

“The degree you got in the 1970s and ‘80s cost less” than today’s degrees, Boedy said, joining Kimbrough in calling for more leaders who will advocate for higher education as a public good.

The high costs of college impact many low-income families and students of color more than other families, Kimbrough said. Some start with less wealth and therefore need more loans, he added. “None of that is fair.”

Kimbrough cited a recent report in Forbes on the underfunding for public land-grant HBCUs, often located in smaller towns or rural areas. Some states don’t even meet minimum funding for these colleges to earn substantial federal matching funds, he said.

Poor treatment of educators

Former Georgia Teacher of the Year Tracey Nance said she’d likely never attended college or become a teacher without her relatives’ intervention into a desperate situation as she was growing up. “Not everyone has an Uncle Pete and an Aunt Nancy to come pick them up and whisk them away” to a better school and send them to Furman University debt-free, she said.

Nance said she’s alarmed by new state laws in Georgia and many other states on restrictions on teaching about race — and hostile parents attacking teachers, school boards, and others. “What we’re seeing is false dichotomies all over the place.” Parents and teachers are almost always on the same side, she added.

Recent decisions by the Georgia Professional Standards Commission to banish diversity and equity from teacher-prep program guidelines were “shocking,” Nance said. The policy change says “that (some) people’s experiences don’t matter as much. We’ve worked so hard to teach the opposite of that.” (The Southern Education Foundation opposed these changes.)

Ignoring our historically marginalized students will not make things fairer, she added. “What’s good for our Black and brown students is good for us (white Americans), too,” Nance said.

Then, in longtime AJC education columnist Maureen Downey’s conversation with Sec. Cardona, the former educator and Connecticut state superintendent called on educators to speak up against hostilities and restrictions on classroom lessons as best they can.

“A lot of people have mistaken our selflessness for submission. We know these students, we know what the needs are,” he said. “It’s OK to say teachers should be making a competitive salary, because that’s good for kids.”

The resource issue in schools

He accused leaders in some states of “slow-playing” the use of federal relief funding for education designed to support students’ academic recovery and emotional health. House Republicans just proposed a multi-billion-dollar, 80% cut in federal Title I funding for public schools, he added.

“We need to reclaim our authority as experts in the profession of education,” Cardona said. “It’s time to stand up for public education, because if it wasn’t for that public school I had in my neighborhood, I wouldn’t be sitting here as secretary.”

The secretary had just spoken at the American School Counselor Association convention in Atlanta. He found among the counselors “such optimism, so much love of what they do,” but disappointment that many counselors must work with 400 or more students at a time. “We’re kidding ourselves if we think that’s designed to serve the needs of our students today,” Cardona said.

“When we don’t provide the resources and tools to provide the mental health support… we can’t be surprised when there’s teacher burnout,” he said.

The nation is no longer fighting COVID-19, but “fighting complacency” in the need to improve education and children’s overall well-being. He praised the growing number of community schools across the nation, including some in Georgia, that provide wraparound services and engage families in new ways.

Cardona said he’d met with Sonny Perdue, the former Georgia governor and U.S. agriculture secretary who now heads the University System of Georgia. “This is economic development. When you invest in education, you’re investing in economic development,” he said he had told Perdue.

On race and education

Asked about the Georgia commission’s stripping of any diversity and equity language around teacher-prep rules: “At least they’re saying it out loud now,” he said. “We’ve normalized… gaps in access and achievement… (and) if the pandemic didn’t give us a heightened sense of urgency, this better.”

On claims by governors and other leaders that schools are indoctrinating students in liberal ideology, Cardona responded forcefully. “People love their kids’ teachers, love their kids’ principal,” he said. “I’ve seen teachers save lives… Are we going to spend our energy there, or are we going to spend our energy on helping our kids succeed?”

“We have to stop being so passive” about defending public education, he said. “It is the great equalizer (for) many people in this room.”

He continued: “Want to talk about parents’ rights? We have the responsibility to give parents’ honest information… Let’s talk about what we do with our public dollars, wraparound supports, tutoring” and special education services, he said.

If some federal lawmakers have their way in pulling back billions of yet-to-be-used relief funds for schools, “that means less social workers, less school counselors, less reading teachers, less support for public schools at a time when kids are underperforming,” Cardona said.

And on race as a factor in removing books and classroom lessons from schools: “Come on, Amanda Gorman’s not good for kids? Toni Morrison? A book on Roberto Clemente?”

Leaders should listen closely to today’s students on their needs in education and related issues. He called on students “to create a tomorrow now.” After all, it’s “students who are the customers of… public education.”

Best time to lead?

Cardona addressed questions from a Spelman College student on affordable housing shortages for students and from a former advisor to Atlanta Mayor Andre’ Dickens on the need to get more children of color considered for gifted programs.

He took questions from a Fulton County Schools board member on preparing new teachers better in reading and science and a lack of federal support for local services to students with disabilities. Such services have “not been funded” like they should be, requiring “both sides (politically) to really double down on their commitment to that.”

Cardona also called for paid apprenticeships for teachers-in-training and to “end the days of free student-teaching.” Otherwise, promising future teachers may opt out of the field because they can’t afford to spend more time in classrooms before becoming teachers full-time. Seventeen states now pay prospective teachers during their apprenticeships, he said.

A representative from the Georgia Association of Educators asked Cardona about retired teachers not being able to receive Social Security benefits. And an Agnes Scott College student from north Florida spoke of how her local schools were struggling with few resources and racial segregation — to which Cardona responded that his department’s Office of Civil Rights could investigate if necessary.

Deciding whether to recommend the reopening of schools when there was no COVID-19 vaccine for children were a great challenge, Cardona said. “The challenge we have ahead of us now is as great.”

He added, “I mean it when I said this is the best time to lead. I didn’t say it’s the easiest time.”